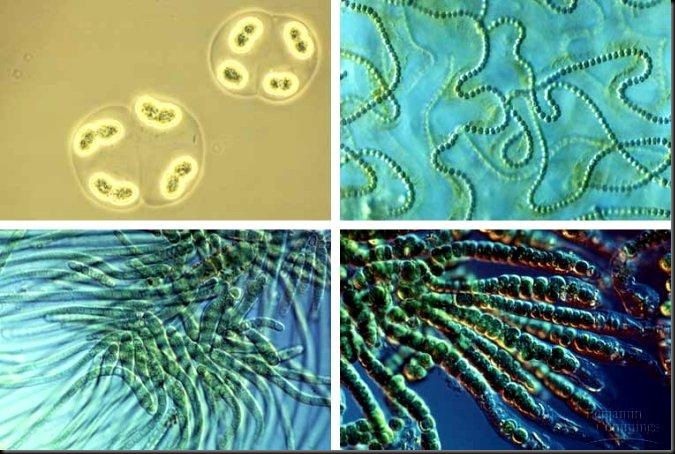

A long-time microbial inhabitant of the human stomach may protect children from developing asthma. Helicobacter pylori, a bacterium that has co-existed with humans for at least 50,000 years, may lead to peptic ulcers and stomach cancer. Yet, kids between the ages of 3 and 13 are nearly 59 percent less likely to have asthma if they carry the bug.

"Our findings suggest that absence of H. pylori may be one explanation for the increased risk of childhood asthma," says Yu Chen, Ph.D., assistant professor of epidemiology at New York University School of Medicine and a co-author of the study. "Among teens and children ages 3 to 19 years, carriers of H. pylori were 25 percent less likely to have asthma."

The impact was even more potent among children ages 3 to 13: they were 59 percent less likely to have asthma if they carried the bacterium, the researchers report. H. pylori carriers in teens and children were also 40 percent less likely to have hay fever and associated allergies such as eczema or rash.

Asthma has been rising steadily for the past half-century. Meanwhile H. pylori, once nearly universal in humans, has been slowly disappearing from developed countries over the past century due to increased antibiotic use, which kills off the bacteria, and cleaner water and homes, explains Dr. Blaser. Data from NHANES IV showed that only 5.4 percent of children born in the 1990s were positive for H. pylori, and that 11.3 percent of the participants under 10 had received an antibiotic in the month prior to the survey.

The rise in asthma over the past decades, Dr. Blaser says, could stem from the fact that a stomach harboring H. pylori has a different immunological status from one lacking the bug. When H. pylori is present, the stomach is lined with immune cells called regulatory T cells that control the body's response to invaders. Without these cells, a child can be more sensitive to allergens.

"Our hypothesis is that if you have Helicobacter you have a greater population of regulatory T-cells that are setting a higher threshold for sensitization," Dr. Blaser explains. "For example, if a child doesn't have Helicobacter and has contact with two or three cockroaches, he may get sensitized to them. But if Helicobacter is directing the immune response, then even if a child comes into contact with many cockroaches he may not get sensitized because his immune system is more tolerant."

In other words, the presence of the bacteria in the stomach may influence how a child's immune system develops: if a child does not encounter Helicobacter early on, the immune system may not learn how to regulate a response to allergens. Therefore, the child may be more likely to mount the kinds of inflammatory responses that trigger asthma.

"There's a growing body of data that says that early life use of antibiotics increases risk of asthma, and parents and doctors are using antibiotics like water," Dr. Blaser says. "The reality is that Helicobacter is disappearing extremely rapidly. In the NHANES IV study, less than six percent of U.S. children had Helicobacter, and probably two generations ago it was 70 percent. So, this is a huge change in human micro-ecology. The disappearance of an organism that's been in the stomach forever and is dominant is likely to have consequences. The consequences may be both good--less likelihood of gastric cancer and ulcers later in life--and bad: more asthma early in life."

Source:ScienceDaily.